Introduction (Abstract):

Football has been the most popular sport in the world for some time now, yet players, clubs, and corporations are only beginning to scratch the surface of it’s commercial potential. Globalization and technological developments have increased the game’s reach to all corners of the world. Companies are racing to capitalize on the popularity of top players to help them engage with potential consumers. Players are being offered sums of money never before seen in sport. Clubs now have unlimited access to different labour markets due to the Bosman ruling of 1995. Public policy considerations, specifically with regards to tax, are having an enormous impact on migration patterns of international superstars. I contend that reducing national tax liabilities of high income foreign workers may attract superstar footballers to play in those countries with favourable regimes. Furthermore, attempting to tax these players will ultimately prove fruitless. The lack of coordinated tax settings, and a patchwork of regulation governing image rights makes it close to impossible for national tax authorities to successfully prosecute those who evade tax. The grey area between tax avoidance and tax evasion has never been larger. The expertise of creative tax lawyers and accountants have made loopholes the norm, and without more certainty regarding image rights, these (arguably) shady practices will continue. Therefore, countries that wish to reap the monetary benefits of having such players should follow the lead of countries like Italy, who have essentially allowed foreign income to go untaxed, minus a small fee. That policy choice indisputably will have played an integral role in Ronaldo’s decision to join an Italian club. Juventus will now be positioned to grow their brand globally and leverage his image by using multiple channels that will focus beyond the sale of tangible goods that are more traditionally associated with football clubs. Barring an unforeseen injury (and maybe even despite one), the team is well positioned to generate a positive ROI from their star player

History:

Effect of the Bosman Ruling:

The globalization of football was partially fuelled by the Bosman Ruling in the European Court of Justice in 1995. It was concerned with freedom of movement for EU workers. The ruling lifted pre-existing restrictions on player mobility, providing a fascinating backdrop to analyse the interaction between taxes and migration. This change revitalized the negotiating power of players, and is largely responsible for the exponential growth in wages of top players. Tax induced migration should be a concern for all public policy makers, particularly where tax rates differ substantially across countries and migration barriers are low, as is the case in the European Union.

The European Football market provides an excellent laboratory/vacuum for the study of migration. International mobility is high among footballers, as there are a number of teams across the globe (mainly Europe) that compete in a labour market with a rigid demand. The result is an ability sorting effect, where a marginal upgrade in talent can be the difference between Champions League glory and a quarter final exit. One of the attractions of football is witnessing the stark differences between player’s ability at the highest level. Since customers are willing to pay more for higher quality athletic competition, the demand for players ultimately rests on their marginal contribution to product quality. From a team perspective, league titles and trophies are often the decider of prize money, sponsorship dollars, and brand awareness. The players are paid for their contributions relative to the marginal upgrade of value from a hypothetically average replacement player, making players like Messi and Ronaldo the ultimate jewels in the sport.

European football provides a useful analysis; high salary footballers often attract the tax rate of the highest income bracket for the countries they are playing in. Therefore this type of study can be crucial to understand trends at the upper bound of the migration response to taxation of the labour market as a whole. This is helped by the extensive amount of publically available data in football about players, transfer fee’s, wages, contracts, et cetera.

There is compelling evidence to suggest a link between taxation and international migration. The Bosman Ruling has compounded this effect. Appendix A identifies the correlation, where a decrease in tax rate can be shown to attract higher quality foreign talent. The number of foreign players playing abroad greatly increased Post-Bosman, and it has had a disproportionate effect on the top contestants, where revenue has become concentrated.

In 2018, there was £430 million spent on transfers, and the amount spent has been steadily rising since the Bosman ruling.

Beckham Law:

In 2004, the Spanish government approved an inpatriate regime (commonly referred to as the Beckham law) with an objective of attractive foreign talent to Spain. Tax rates of the top bracket for non-residents were reduced to 19-24.75% depending on the fiscal year, while the residents tax rate remained at 50%. This law stayed in place until 2010, when it was removed for those making an income greater than €600,000.

The act had its intended effect. David Beckham, arguably the most famous footballer in the world at the time, arrived at Real Madrid at the beginning of the 2004-2005 season. By the end of the 2005-2006 season, Real Madrid had become the world’s richest club by revenue as a result of the significant increase in commercial appeal rather than their on-field performances, particularly in China.

Cristiano Ronaldo also benefitted from the tax regime. He arrived at Real Madrid in 2009. Foreign players who moved to Spain by the end of 2009 were granted a transition period that expired on Jan. 1st 2015. It was this regulation that Ronaldo and his advisors ultimately took full advantage of, but this will be further explored later in the paper.

Image Rights:

Our culture is generally referred to as an “Instagram Age”. Images of particular individuals can be of sizable commercial value. In a footballing context, image rights include a player’s name, nickname, voice, signatures, and all other characteristics unique to the player. Deals involving a player’s image rights enable the them to exploit their likeness for commercial value through sponsorships and endorsements. If the player’s image has independent commercial value, the player will often seek to create an Image Rights Company (IRC). Creating IRC’s can often have tax advantages, as they are taxed at corporation tax rates. An example of the types of savings this can lead to is provided for in Appendix B.

The legislation governing image rights is underdeveloped, and jurisdictions often fail to define what they are, or consist of a patchwork of legal rights with many gaps in protection. In the UK for example, the courts have resisted attempts to create a distinct image right, such as in the case of Rihanna and Topshop. It involved the first successful celebrity case of it’s kind, where the Court of Appeal ruled that marketing merchandise with Rihanna’s likeness without her approval amounted to “passing off”. However, they made it very clear that the decision does not create an image right in the UK. The court emphasized that there is no image right in English law that allows a celebrity to control use of their image, and that the decision was largely confined to a very specific set of facts that included Rihanna’s commercial activities in the fashion world.

The United States has made a number of developments to this area of law, as publicity rights have been recognized, and image rights have been given statutory protection in certain states.

Exploitation of Image Rights:

Image rights deals are perfectly legal, however they operate in the grey area that often delineates tax avoidance and tax evasion. This is the sweet spot for player agent’s and their financial advisors. A series of leaked football documents (termed “Football Leaks” due to it’s parallels with “WikiLeaks”) arrived at the hands of a number of of reputable news outlets, thanks to Rui Pinto, a whistle-blower who has now been extradited from Budapest to Portugal facing a number of charges relating to the release of secret information about the financial dealings of clubs. His efforts, as well as the help of the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) and their partners are responsible for much of the research done for this paper. There are 10 terabytes of data, 6 of which have yet to be released. It is likely that the release of the remaining information will depend on the outcome of Rui Pinto’s case, as he is purported to be the only holder of the relevant encryption key. Thankfully, French investigative authorities rushed to Budapest and managed to make a copy of the Football Leaks data, amid fears that the information could be destroyed in Portugal. His work has exposed many illicit practices that affect world football.

There arises a basic formula for star players to avoid paying high taxes. The first step is creating a company in Ireland where payment will be forwarded for marketing of his likeness. This is because Ireland has the lowest corporate tax rate in the European Union (12.5%). Big corporations like Nike and Adidas are generally squeamish when it comes to making payments to companies located in the Caribbean, as this often raises red flags in publically traded companies. These Irish companies served as a buffer between the players and large corporations or football clubs like Chelsea and Manchester City who were prepared to make large payments by paying for their image rights. The money was then cleared through tax havens in countries like the British Virgin Islands or Panama and often conveyed back into European bank accounts.

Players using Image Rights: Cristiano Ronaldo:

This type of tax structure drew significant attention with the news that Cristiano Ronaldo had accepted a €19,000,000 fine, in exchange for a 23 month suspended prison sentence (Jail sentences of 2 years and under are generally suspended for first time offenders in Spain). Ronaldo may consider himself lucky to have dodged prison time. Of the four accusations of tax fraud made against him, three were considered by prosecutors to be “aggravated”, thus carrying a minimum sentence of two years each. Ronaldo pleaded guilty to these four counts of tax fraud, while the amount of tax fraud he admitted to defrauding was reduced from €14,800,000 million euros to €5,700,000 million as part of the agreed upon deal with the prosecution. A document written by the prosecutor stated that Ronaldo was accused of making use of a corporate structure created in 2010 to hide from the tax authority income generated in Spain through image rights.

One of the largest examples of tax evasion that Ronaldo was found guilty of was in regards to a transaction he had made at the end of 2014. Ronaldo’s transition status for the Beckham Rule was coming to the end, meaning the tax rate he paid was going to jump from 25% to 50% on the money he earned in Spain. In December of 2014, Ronaldo sold his image rights to IRC’s for the years 2015 to 2020 for close to €75,000,000. The buyers of the rights were two newly established shell companies in the British Virgin Islands called Arnel and Adifore. A payment of €63,500,000 was made to Adifore for Ronaldo’s global image rights. Arnel received payment of €11,200,000 for use of his Spanish rights. This payment made to Arnel was the only listed revenue on Ronaldo’s tax return associated with his marketing activities in Spain. It appears as though that the €63,500,000 payment received by Adifore went untaxed.

The declaration of income for image rights revenue of future years is not acceptable by any tax authority. Ronaldo was not free to declare income for 2015-2020 in 2014 simply because he preferred the tax rate in 2014. This is one of a plethora of examples of how creative football agents can redirect capital flows to avoid tax. Furthermore, Ronaldo was chastised but not in any significant manner. His prison sentence was a mere formality, and the fine he paid was in all likelihood substantially less than the savings that arouse as a result of this tax structure.

Domestic vs Foreign Income:

Income is deemed to be foreign sourced if the activity that generated the revenue is carried out outside of the resident’s country. Article 17 of the OECD Model Convention with respect to taxes on income and on capital regulates the allocation of income derived by sports persons and entertainers. It states that income derived by a resident of a contracting state, a sportsperson or entertainer, with personal activities exercised in another contracting state, may be taxed in that other state. The scope of Article 17 is rather to prevent tax avoidance where income in respect of personal activities of a sportsperson accrues not to the sportsperson, but to another person. The limited scope of oversight from the OECD allows creative agents and accountants to take advantage of the current patchwork of laws that govern image rights. Footballers often receive remuneration in the form of sponsorships, advertising fees, merchandising payments, or sale of their image rights. The guidance offered by the OECD is that where payments are not closely connected with the sportspersons performance in a given state, the relevant payments will not be covered by Article 17. It is herein that the difficulty lies.

The issue with image rights is determining which activities are foreign sourced and which are domestic. The Spanish Tax Authorities have an argument that Ronaldo’s Nike boots are generating income in Spain, but Ronaldo may argue that as he is such a global brand, the majority of the commercial value derived from his endorsement income should be allocated as foreign income. There is little to no pressure from any country’s tax authority as to how image rights income should be sourced. France is on the forefront of trying to develop a comprehensive image rights regulatory framework. Their goal has been to improve the competitiveness of French professional sports (mainly football) by reducing the social barriers that may constrain clubs.

Agents: The Facilitators

Jorge Mendes’ is the closest approximation to the “Cristiano Ronaldo” of football agents. His clients are some of the world’s top talents, including Cristiano Ronaldo, Jose Mourinho, Angel Di Maria, James Rodriguez, Diego Costa, Radamel Falcao, Filipe Luis and many more. A common thread between the players I have listed is that they have all been found guilty, or are currently in the process of court proceedings in regards to tax evasion.The Spanish Tax Authority have been investigating the tax structure’s used by these players. All have been accused of using offshore companies to receive payments in regards to their image rights. Generally, the companies have been located in the British Virgin Islands, and are cleared through Ireland, by way of Multisports Image and Management (MIM) and Polaris Sports. These are the companies that were the official image rights holders of Cristiano Ronaldo and Jose Mourinho, some of Mendes’ highest profile clients. Although Cristiano’s name does not appear on any of the company’s records, “Cristiano Ronaldo” and “Cristiano Ronaldo Legacy” are registered trademarks owned by MIM. The allegations made against them have been that these Irish companies are being used as conduits with the purpose of evading taxation at source. Polaris was the only company that employed any real personnel. This became relevant as the Spanish Tax Authority used information about how active a “conduit” company was, and the number of employee’s at these companies to help decide which cases to prosecute. Where a company did not employ any real personnel or conduct any genuine commercial activity, the tax authority would allege tax evasion.

Transfer Fees:

Agents are paid upon negotiation, or renewal of a contract. There are typically two steps for which an agent should be paid: the agreement of a transfer fee, and the agreement of terms between the signing club and the player. Transfer fees have been steadily rising since the Bosman ruling, and an agent’s cut can be huge. Super agent Mino Raiola received a reported £41,000,000 commission for his role in facilitating the £89,300,000 transfer of Paul Pogba from Juventus to Manchester United. Since 2016, there have been 6 agreed transfers fees of over €100,000,000.

Historically, there has been an issue of who is responsible for payment of agent commissions, players or the clubs. Common sense would dictate that agents are working on behalf of the players, but that is not always the case. Agents can be compared to elite recruiters, often with unfathomable influence. For example, Jorge Mendes has recently teamed up with Chinese investors to create a strategic partnership called “Fosun International”. The Fosun group has assets worth more than $10 billion (USD). Their goal is to create a network of clubs and academies where Mendes can use his influence to place players. They have found that trading in talent is often more profitable than owning soccer clubs. Third party ownership (TPO) was historically a very lucrative method for enormous profits. This is where a player’s economic rights are owned by a third party (usually an agent or investor). The eventual sale of a player would see the investor receiving a portion of the agreed upon transfer fee. The exploitation of TPO was recognized by UEFA, and banned in 2012 before becoming completely phased out in 2015. Yet Mendes, as expected, found a creative way to continue asserting his influence. The Fosun group purchased English football club Wolverhampton Wanderers in 2016. Since that point, Wolverhampton has spent over £65,000,000 on buying new players (more than what they paid for the club). The new manager appointed was a former goalkeeper in the Portuguese league, who also happened to be Jorge Mendes’ first ever client. Football Leaks documents have now shown that Fosun International owns a 15% stake in Gestifute Agency, which is owned by Jorge Mendes. This is in breach of Football Association (FA) rules which state an agent cannot influence a club’s conduct.

Agent Fees:

A common method for agents and players to reduce tax liability is claiming they work on behalf of a team, rather than the player. Club’s are entitled to write off payments made to agents as general business expenses’ taxed at the corporate rate, only if the agent is deemed to be working on behalf of the club. If the agent is deemed to be working on behalf of the player, the player will be liable to paying sales tax and income tax on that commission, with the clubs paying its social security contributions. The key question becomes, was the agent representing the club, or was he representing the player? It is quite often easy to spot when a well known player agent suddenly seems to be working on behalf a club, but the situation becomes more difficult when the agent is representing both club and player. In the UK, the standard assumption is that 50% of the work is done on behalf of the club and 50% of the work is done on behalf of the player, barring any evidence to rebut that presumption. Even in cases where it is clear that the agent is working on behalf of the player, agents still try to have clubs take responsibility for the payment of commissions. This was partially what led to Jose Mourinho’s conviction of tax fraud. Football Leaks documents revealed his contract guaranteed that 90% of the fee’s paid to Jorge Mendes would be paid by Chelsea Football Club, with Mourinho (via Mendes) begrudgingly accepting the payment of 10% of the commission. An example of the types of tax savings that can be garnered from this technique has been included in the appendix.

The HMRC has begun to crackdown on these types of practices. Nearly 2,000 football agents have received letters that they may face tax investigations over serious allegations of fraud. They are currently investigating 38 agents, 40 clubs, and 173 players, and are considering the opening of further investigations. Since 2015, the government has received an additional £350,000,000 of tax revenue from football. £211,000,000 was the amount paid to agents in 2017-2018, and the HMRC are working on ensuring the correct amount of tax has been paid on that income.

Football Clubs: Using Image Rights

Football clubs are using image rights to their advantage. In 2009, UEFA approved the introduction of Financial Fair Play rules, which was meant to drastically effect how clubs conducted business. The rules provide for the application of sanctions to punish clubs whose expenses exceeded their revenues over several seasons. Possible sanctions include disqualification from European competitions, withholding of prize money, and transfer bans.

There are a number of clubs which are notorious for overspending, such as Chelsea, Manchester City, and Paris Saint-Germain (PSG). These clubs are constantly in search of creative ways to attract top players. The case of Sports Club plc v Inspector of Taxes was a landmark decision in UK tax court. Arsenal Football Club succeeded in making payments to an off-shore company with regards to the image rights of their players David Platt and Dennis Bergkamp. The payments were considered as capital sums for tax purposes, and therefore non-taxable as income. The legal difficulty comes with the valuation of these rights. The unpredictable nature of football can lead to a wide variation in figures. Valuations are made on a case by case basis, though should ideally should be based upon predicting future revenue streams from the commercialization of the footballers image, while discounting risk factors such as injury and early retirement. The goal is to determine a fair market net present value. However, star players are few and far between, thus giving them substantial leverage when negotiating the amount and manner in which they are to be paid.

Clubs often buy a percentage of a player’s image rights as part of their salary. This has a number of advantages for both parties. The player benefits, as this income can be routed through Ireland for minimal tax obligations. The clubs also benefit, as instead of a salary expense, they have an intangible asset with commercial value on their balance sheet. Clubs are then under less pressure from potential FFP violations. While Ronaldo was contracted with Madrid, he was required to pay 40% of his image rights to the club for every dollar earned past €15,000,000. This also allows Real Madrid to pay the corporate tax rate on these payments, which is lower than the income tax rate. While this business practice is completely legal, it is common practice for big clubs to write off millions of euros from their balance sheets, stemming from the losses of their image rights payments. An example of this can be seen in Manchester, who have been desperate to add revenue and cut expenses in recent years, to comply with FFP measures. In May of 2013, Manchester City sold the image rights of it’s top players to a new company called Manchester City Football Club (Image Rights) Ltd. From 2013 to 2017, that image rights company showed losses of over £70,000,000. This practice has been picked up by domestic tax authorities, such as Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC). The HMRC generally allows for up to 15% of a player’s income to be derived from their image rights, with an exception of 20% available in the circumstances of a global celebrity. Before the 15% rule came into force, the HMRC was “reasonably successful” in arguing that image rights payments of 40-60% should have in fact have been declared as salary, and taxed as income. It is difficult to avoid taxes on salary paid by the club, as the rules in place are clear, with transparent methods of tracing payment. However, with regards to image rights income, skilled tax lawyers are truly gifted at the art of devising elaborate structures that protect their clients from potential criminal liability, while simultaneously providing enormous savings.

Overvaluation of Sponsorship:

Financial Fair Play has forced teams to take drastic measures to comply with the regulations laid out. PSG and Manchester City are two of the primary culprits. UEFA’s regulatory arm, the Club Financial Control Body (CFCB), took the view that the Abu Dhabi sponsors of Manchester City and the Qatari Tourism Authority’s sponsorship of PSG were vastly inflated. The fair market value of the relevant Manchester City sponsorships according to the CFCB were €6,100,000 and €6,700,000 respectively whereas the sponsors were paying a combined €40,000,000 for these rights. PSG was even bolder. The sponsorship they received from the Qatar Tourism Authority was deemed to have a fair market value of €5,500,000, yet the QTA paid €100,000,000 in 2017. The following year, the amount paid by the QTA increased to €145,000,000. The additional €45,000,000 of sponsorship seems only natural, as this was the year PSG completed the signing of two of the worlds most talented and marketable footballers, Neymar and Mbappe, for a combined €402,000,000 (€222m and €180m respectively). In the cases of both Manchester City and PSG, the relevant sponsors had direct ties to the owners of the clubs, yet Tobias Troeger, a professor of Law at Goethe University in Frankfurt said that sponsoring companies would not be breaking their fiduciary duty to shareholders by overpaying for sponsorships, provided that the shortfall be covered by another party and the director’s believed that in it’s entirety the transaction was in the best interests of the company. Luca Enriques, a professor of Corporate Law at the University of Oxford added that he could not see how any third party could be subject to football’s jurisdiction. In a leaked email, Manchester City CEO Ferran Soriano said that he and UEFA president Gianni Infantino had come to an agreement to instruct lawyers of Manchester City and UEFA to negotiate a settlement that amounted to “more than a warning” but that “does not affect dramatically MCFC business”. On April 30th, 2019 it was announced that PSG will have to sell €60,000,000 worth of players in exchange for a lack of sanctions. On May 2nd 2019, it was reported that Qatar was considering pulling funding from PSG due to their failures in cup competitions. The biggest disappointment of PSG’s season was losing in the quarter-final of the Champions league on a 94th minute penalty controversially awarded penalty by the Video Assistant Referee (VAR). The Champions League is considered the most prestigious trophy in European club football. Their loss, and subsequent threat of pulled funding illustrates the stakes involved for all parties, despite games being decided on the smallest of margins. On May13th, 2019 the New York times reported that UEFA Investigators are seeking to ban Manchester City from the Champions League, as a result of their failure to comply with FFP.

Opaque Structures:

There are a number of vulnerabilities that make football attractive for criminal activity. The market is easy to penetrate. Little beyond money is required to get involved, and purchases of football clubs often grant access to local politicians and businessmen. Complicated networks of shareholders and the lack of transparency between substantial money flows facilitates the concealment of fraudulent activity. Football clubs depend on sponsorship to generate revenue. If there is no background check done on sponsors, then criminals can use sponsorship as a pathway to legitimate business (i.e. money laundering). Competition is stiff in football, with minor differences in outcome leading to enormous differences in earning potential. This incentivizes clubs to engage in riskier activity. Private investment banks have recently entered the industry by providing short term loans to cash strapped clubs. Teams have been willing to pay interests rates of up to 10%. Conversely, banks have been sending agents door to door to find teams to do business with, as football provides the perfect investment opportunity for those who have millions parked in offshore tax havens. An example of this can be seen during the sale of Sergio Aguero from Athletico Madrid to Manchester City in 2011, for a fee of €36,000,000. One third of the fee (€12M) was paid up front, with the remaining €24,000,000 set to arrive in 2013. Immediately after the sale, the CEO of Athletico Madrid borrowed the outstanding €24,000,000 from a company in the British Virgin Islands called Morehouse Limited. The FA demanded to know the company’s ownership structure, but the company’s lawyers resisted. Ultimately, when faced with the possibility of Aguero not being able to play for Manchester City, the company relented and disclosed that the owner of the company was a prominent UK billionaire whose fortune came from his betting shop empire.

Vulnerabilities of Football:

Match fixing is considered to be one of the largest problems facing football. There have documented cases of match fixing in the professional leagues of Italy, Spain, England, Germany, and even in the World Cup. This issue is outside of the scope of this paper, but the introduction of criminal funds into football plays a large role in this phenomenon.

There is an inherent unpredictability of football, which can justify the payment of seemingly irrational sums paid for players. The discovery and training of talent can ultimately lead to colossal profits. The increasing number of transfers, and prices of these transfers has provided investors with ample opportunities to recoup their investments. The free flow of money across borders fall largely outside the purview of national and supranational institutions, making this an attractive method for criminal organizations to launder money. In Turkey, the national football federation allowed clubs to make payments to over 30 unregistered intermediaries for player transfers. In five of the 30 cases, there is a discrepancy between the fee stated in the federation’s records and the real contract value, which in each instance is considerably higher. This is common practice, even among some of the world’s top talents. In one of the few instances where these issues have been prosecuted, the agent of Luka Modrid, the winner of the 2018 Ballon d’Or was found guilty of funneling half of the €21,000,000 transfer fee paid by Tottenham Hotspurs to Dinamo Zagreb into his private bank accounts. A potential solution for payments made to unregistered intermediaries would be the creation of a “clearing house” to process all transfer fee payments, including the fees agreed between clubs, as well as payments made to agents. Significant roadblocks would have to be addressed before this can be implemented.

Ronaldo Economics

The best footballers are some of the world’s biggest stars. The proliferation of digital technology has significantly increased the reach that these players have. As such, companies are hungrier than ever to associate with their brands. The nature of this income (usually hard to pin as domestic) makes it straightforward for creative tax lawyers and accountants to create structures that minimize their tax and (potential) criminal liability. Agents are increasingly emboldened to adopt high risk, high rewards strategies, as the potential sanctions they may suffer pale in comparison to what they stand to gain. Governing football bodies have little to no jurisdiction to punish these actors, and national tax authorities do not have the resources or legal standing to properly deter tax evasion. The regulations that govern image rights vary from country to country, and lack any degree of certainty. While countries like Spain and England have limited the percentage that clubs can pay players with image rights, this does not have any impact on the revenues they can expect to receive from abroad. A countries tax regime has become one of the most important factors that players must consider before choosing their next destination.

Attracting Top Talent – Italy:

In 2017, Italy’s new budget included a favourable set of rules targeted at attracting high net worth individuals that were willing to make Italy their new tax residence. It is available to those whose residence was outside Italy for at least 9 of the last 10 years. The regime allows payment of a €100,000 flat tax on their overall foreign sourced income. This applies to income tax on image rights, foreign investments, wealth tax on real estate, and financial investments owned outside of Italy. Another benefit of the regime is that individuals are not required to declare their foreign investment on their Italian tax return.

In 2018, Juventus (Turin, Italy) announced it had signed Cristiano Ronaldo from Real Madrid for a fee of €105,000,000. They committed to paying him an annual salary of €30,000,000. As this income is domestically sourced, Ronaldo will be paying a 43% tax rate on his salary as part of Italy’s top highest earning bracket. However, the vast majority of his remaining income (mostly endorsements) will likely be treated as foreign sourced due to his global popularity, and he will only pay an annual €100,000 fee. Forbes estimated that Ronaldo’s 2018 income was about €92,000,000. Ronaldo’s transfer to Juventus coincided with the end of his “Beckham Law” benefits, and the culmination of his legal battles over his tax returns.

Football clubs have a rigid labour demand, and location elasticity’s are greatest at the top of the ability distribution. Clubs are willing to spend exorbitant amounts of money to attract these sorts of players. Ronaldo has over 330 million followers on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. A report by KPMG titled “Ronaldo Economics” detailed the commercial potential that this signing might have for Juventus. Merchandise sales, proceeds from match days, broadcasting deals, and kit sponsors are all likely to significantly increase. There is also the opportunity to increase the sponsorship they receive internationally on the back of Ronaldo’s image. 40% of Juventus’ sponsors are Italian based, whereas other big clubs such as Manchester United, Barcelona, and Real Madrid hover around 15%. Ronaldo’s arrival gives Juventus newfound leverage with the negotiation of their sponsors and licencing agreements.

Prior to the rumours of Ronaldo’s transfer, Juventus’ (JUVE) stock price was at €0.66, and jumped to €0.898 at the time of the official announcement. On April 16th, the stock was at a peak of €1.71, before dropping to €1.39 the day after their defeat to Ajax in the Champions League.

I believe that Juventus’ shareholders will be able to capitalize on their investment in Ronaldo, provided that their business strategy effectively makes use of the increase in social media following they can expect to receive. The Italian government will benefit from an excess of €12,500,000 of tax revenue that they can expect from Ronaldo’s playing salary at the club. Ronaldo himself will benefit greatly, as the fortunes he earns from his image rights abroad will be essentially tax free, relieving him of the burden of manipulating his income through complicated tax structures. Win-Win-Win for the club, country, and the player.

Lessons from Spain:

It is clear that Spain’s recent tax increases have discouraged footballers from coming there (or causing them to leave). Their recent push to increase the number of tax investigations into players certainly does not help either. The President of La Liga, Javier Tebas, reiterated this sentiment in an interview, stating that he believed that Spain’s high tax rate contributed to Ronaldo leaving and was preventing the league from growing. Shortly after this interview, Javier Tebas wrote a letter to all 20 La Liga clubs declaring the leagues opposition to the 2019 budget, which he estimated could cost clubs a combined €80,000,000. The proposed tax reforms would see a 2% increase on those making an income greater than €130,000 a year, and a 4% increase on those making in excess of €300,000 a year. He predicted that this would mean the departure of about 20 elite players from the league.

Reducing tax rates and regulation has historically been used by countries to attract foreign investment from multinational corporations. That understanding needs to be expanded to include enticement of high income individuals, particularly foreign footballers. While their assets may not match those of MNE’s, their mere presence can significantly increase the commercial opportunities available to all parties involved. They face little to no migration barriers thanks to the Bosman ruling. It is far easier for footballers to pack their families bags and relocate to a new world class city than it is for corporations to relocate factories. Rigid labour demands in football create an environment where highly skilled recruitment agents can canvass Europe’s top team in search of the best situations for their clients, both on and off the field. Some top players like Messi have decided to stay with one club their entire career. Other players like Cristiano Ronaldo have moved from Portugal to England to Spain to Italy. In both instances, the players can expect to be compensated generously. Messi recently renewed his contract at Barcelona despite his recent conviction of defrauding Spain of taxes through shell companies in Belize and Uruguay. He has become the first player to be guaranteed an annual income of more than €100,000,000 in a deal that lasts until 2021. He has been guaranteed to receive €450,000,000, which includes Barcelona’s payment of Messi’s tax debts. While Ronaldo will not earn as much income as Messi from his club, his move to Italy guarantee’s that the revenue he earns from his deals with Nike, Toyota, Herbalife, Emirates, and Tag Heuer (to name a few), will largely go tax free.

As the money invested in football increases, the line between sports and entertainment begins to blur. Smart clubs understand that acquiring a star player does more than increase their team’s chances to win any given match, but also allows clubs to leverage their new signings into improving revenue streams and engaging with consumers. Engaging with users on social media also allows clubs to break into untapped markets like Asia. Team revenues have been climbing over the past two decades, and there has never been as much money in the game as there is today.

Ideal Tax Settings (For Attracting Talent):

Reducing foreign income tax rates relative to domestic rates is a good economic strategy for countries seeking to attract talent. From a worker’s standpoint, domestic labour and foreign labour are substitute goods, therefore if one is being taxed then both should be. However, the general theory of nonlinear taxation would support taxing a group greater than another, if the marginal rate of substitution of the first for the second increases with ability. Players are paid according to their marginal increase in ability over a replacement/average level player. The result is that top players have a monopoly over the most coveted abilities. Rewards at the top are disproportionately high, and rewards at the bottom are disproportionately low. People are willing to work for very little just for the opportunity to compete for the chance to work in one of these top jobs. In most markets, more competition would attract more applicants to do these types of jobs and ultimately reduce wages, but in a winner-takes-all market, this does not happen. This reflects the economics of businesses in entertainment and sport that are commonly celebrity dominated. Globalization has expanded the market for skills, increasing the opportunities for the rich to become richer. A tax regime that attracts world class players will likely have its intended effects, as well as the likelihood of positive spillover effects towards other domestic stakeholders.

Italy’s decision to exclude foreign income from taxation (providing it has been taxed in another jurisdiction) had it’s intended effect when Juventus signed Ronaldo. The commercial upside for Italy has been clear. Within the first 24 hours of his signing, the team sold 520,000 Ronaldo kits for €105 apiece, a total of more than €61 million. While some hardliners may be critical of Italy for allowing Ronaldo to collect his foreign income essentially tax free, the positive spillover effects that his presence will have on the Italian economy is undeniable. Another example of positive externalities can be seen from KPMG’s report titled “Ronaldo Economics” which states that Ronaldo’s arrival will result in a vastly greater income generated from the Serie A’s title sponsor. The Italian league has not performed up to it’s capabilities in the past decade commercially or competitively, and Ronaldo’s arrival has injected newfound optimism about it’s direction moving forward.

UK residents who are non-domiciled do not have to pay tax on their foreign income. If the source of the income is within the UK, their foreign income would be taxable at the highest rate of 45%. The UK has thus far been fairly lenient with it’s prosecution of image right’s companies, which may be partially why the UK has managed to attract a steady diet of top players.

Germany does not include any special tax regimes for sportspeople. It taxes the sale of image rights as a capital gain (45%) and with a trade tax (15%). This is an intentional policy decision by the German government. Top foreign players in England have begun to displace younger domestic players. The German league is proving to be an attractive landing spot for talented young English players to develop their game. This encapsulates the downside of attracting foreign talent. Domestic talent can suffer when they lose playing time and other developmental resources to more established players. This is a factor that policy makers must keep in mind. The counter argument would be that the increased quality of play as a result of the arrival of star players could potentially raise the level of skill of their new peers.

Spain went from one of the most attractive destinations to foreigners to one of the least enviable. Their removal of the Beckham Law will in all likelihood reduce the number of top players that join La Liga. While it may have been an informed policy decision, it is difficult to imagine a scenario where the economics support these changes, though socio-political factors are often involved.

Lack of a Better Alternative:

I contend that national tax authorities do not have the resources or necessary legal standing to adequately ensure that players are paying the taxes they believe to be correct in accordance with national laws. The line between tax avoidance and tax evasion has become entirely convoluted with the number of structures available to players that can reduce their tax liability. When coupled with a lack of certainty to how income should be properly sourced, national tax authorities are overmatched. Even if countries attempt to prosecute offenders (like in Spain), the reality is that players will generally walk scot-free. Ronaldo had the most transparent and egregious case of tax fraud in football history, yet received no jail time. Barcelona agreed to pay Messi’s outstanding tax debts. Agents will continue to assert their influence on the game, directing players to the most profitable destinations. Players are incentivized into stashing money in complicated tax structures, and it is unlikely that they will be appropriately punished. A way to curtail this black market would be to follow Italy’s lead in offering highly skilled foreign nationals a flat fee in exchange for very limited oversight and taxation of their foreign income. Doing so may have been the difference between attracting a player like Ronaldo, and not. While it is impossible to truly understand Ronaldo’s motives for joining Juventus, I strongly believe that if speaking truthfully, he would state that tax incentives were one of his primary considerations, especially considering the years long protracted legal battle he had with Spanish authorities. I imagine that removing the fear of “Big Brother” watching his international finances would be quite a good stress reliever.

Members of a recent European Parliament inquiry have branded FIFA and UEFA as enablers of a corrupt system that allows players and agents to avoid paying tax. Members were frustrated with Barcelona’s social media campaign with the hashtag “#WeAreAllLeoMessi in the wake of his 21-month prison sentence. Gregor Reiter of the European Football Agents Association noted that sanctions were difficult to implement due to the uncoordinated rules across the continent. FIFA’s head of global player transfers and compliance also reiterated that this was a matter for national legislation. The final report from their investigation will be submitted later in 2019.

I believe that countries that want to optimize tax revenue would be well served by reducing taxes on high income foreign nationals. Attempting to tax them may bear fruit, but likely runs counter-productive if your goal is to attract talent and capital. The same can be said with MNE’s. The more tax and regulations they are faced with, the less likely they are to do business in your country. Globalization has allowed in-demand actors to cherry pick their destinations. The enormous sums of money involved in football make it a domain that countries with an interest in soccer should seek to enter, by way of curated tax policies.

Thesis written by Karim Eshqoor, Head Lawyer at Barbarian Law

Bibliography

Aarons, Ed. “Fifa and Uefa Accused of Being ‘Enablers’ of Tax Evasion in Football by MEPs.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 27 Sept. 2017.

Arce, Juan Manuel Serrano. “Spanish Tax Authority to Inspect Four More Jorge Mendes Clients.” AS.com, Diario AS, 23 June 2017.

“Article 17.” Articles of the model convention with respect to the taxes on income and on capital, OECD, 2003.

Ahmed, Murad. “Football Image Rights Payments Back in Focus after Mourinho Report.” Financial Times, 6 Dec. 2016.

Ahmed, Murad. “How a Passion for Football Kicked off a Stellar Legal Career.” Financial Times, 3 Feb. 2019.

Badcock, James. “Why Are Spanish Football Stars in Legal Trouble?” BBC News, BBC, 18 June 2017.

Belcher, Chris. “What Are Image Rights in Football and How Are They Taxed?” Mills & Reeve, 12 July 2016.

Bergin, Tom, and Cassell Bryan-Low. “How a Soccer Agent and Chinese Billionaire Aimed to Trade in Players.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 3 Jan. 2019.

Blackshaw, Ian. “Understanding Sports Image Rights.” WIPO, 2017.

Blunt, Michelle, and Sabrina Tozzi. “Commercialising Image Rights: Reaching for the Stars.” Lexology, 1 Sept. 2016.

Buschmann, Rafael, et al. “FC Barcelona Star Lionel Messi: Tax Troubles, an Audit and a 100-Million-Euro Contract.” Der Spiegel, 15 Jan. 2018.

Buschmann, Rafael, et al. “New Tax Problems: Lionel Messi Paid around 12 Million Euros in Back Taxes – Der Spiegel, 12 Jan. 2018.

“Buying Time: The Scramble for Fresh Capital in Professional Football” Der Spiegel, European Investigative Collaborations, 16 Nov. 2018.

Carpenter, Jennifer L. “Internet Publication: The Case for an Expanded Right of Publicity for Non-Celebrities,” Virginia Journal of Law & Technology vol. 6, no. 1 (Spring 2001): p. 1-20.

Carnero, Carlos, and Eduardo Montejo. “Why Spain’s Approach to Taxing Image Rights and Agency Income Is Discouraging Overseas Footballers.” LawInSport, 1 March 2019.

“Champions League Stars Bring Their Talent Home.” Financial Times, 13 July 2018.

Collet, Michael. “Separate Sports Image Rights Agreements with Employers Now Possible in France.” Separate Sports Image Rights Agreements with Employers Now Possible in France, CMS Bureau Francis Lefebvre, May 2017.

“Cristiano Ronaldo’s Offshore Adventures.” Football Leaks: Cristiano Ronaldo’s Offshore Adventures – The Black Sea, European Investigative Collaborations, 2017.

“Cristiano Ronaldo Renews Real Madrid Contract until 2018.” MARCA, 15 Sept. 2013,

“Cristiano Ronaldo Agrees Tax Fraud Deal of 2 Years in Jail, Pay $21.9 Million.” Agencia EFE, 15 June 2018.

Delaney, Miguel. “How Bundesliga Interest in English Talent Is Just the Beginning.” The Independent, 16 Jan. 2019.

“Diego Costa Accused of Tax Fraud.” MARCA, 17 Apr. 2019,

“Double Agents: A Handy Tax Trick Used By Agents and Players – Spiegel Online – International.” Der Spiegel, European Investigative Collaborations, 14 Nov. 2018.

Fleming, Nic. “China Welcomes the Real Beckham.” The Telegraph, 26 July 2003.

“Employment Income Manual.” EIM00732 – Employment Income Manual – HMRC Internal Manual – GOV.UK, UK Government, 2019.

“European Commission Upholds Third-Party Ownership Ban.” ESPN, 13 Oct. 2017,

Garcia, Adriana. “Cristiano Ronaldo Move to Juventus Influenced by Spain Tax Rate – La Liga Chief.” ESPN, 19 July 2018.

Garcia, Adriana. “Angel Di Maria Fined €2m in Tax Fraud Case While at Real Madrid.” ESPN

Hill, Declan. The Fix: Soccer and Organized Crime. McClelland & Stewart, 2010.

“Italy Proposes 100,000 Euro Flat Tax to Draw Foreigners.” Yahoo! Finance, 8 Mar. 2017.

“Judge OKs Extradition of Football Leaks Whistleblower.” SI.com, Associated Press, 5 Mar. 2019.

Kellogg, Amy. “Ronaldo’s Big Italian Tax Break – Will the Country Also Benefit?” Fox News, 20 Aug. 2018.

Kidd, Robert. “Premier League Transfer Spending Hits $1.8 Billion But Falls In January, Report Finds.” Forbes, 1 Feb. 2019.

Kleven, Henrik, et al. “Taxation and International Migration of Superstars: Evidence from the European Football Market.” American Economic Review, 2010, pp. 1892–1924.

“La Liga President Says Proposed Tax Reforms Could See Elite Players Leave.” ESPN, 18 Oct. 2018.

Marriage, Madison. “Football Crackdown Nets £330m for HMRC .” Financial Times, 20 Oct. 2018.

“Massive Tax Fraud of Luka Modrić’s Agents Vladica Lemić and Pedja Mijatović.” Nacional, European Investigative Collaborations, 12 Nov. 2018.

“Money Laundering through the Football Sector.” Financial Action Task Force, 2009.

“Money Game: How Top Soccer Clubs Clashed with Sport’s Financial Rules.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters / European Investigative Collaborations, 2 Nov. 2018.

Montejo, Eduardo, and Carlos Carnero. “Comparative Tax Approach of Major European Leagues.” Senn Ferrero Asociados Sports & Entertainment, S.L.P., 2019.

Montejo, Eduardo. “Spanish Tax Situation of Image Rights.” Senn Ferrero Asociados Sports & Entertainment, S.L.P. 2018.

Mount, Ian. “Ronaldo Agrees €18.9m Tax Fraud Settlement.” Financial Times, 26 July 2018, www.ft.com/content/3793076c-90f6-11e8-bb8f-a6a2f7bca546.

Miguelsans, Luis. “How Ronaldo Has Dodged Tax on Image Rights through Irish Company.” Sport English – Real Madrid, 14 Apr. 2017.

Mirrlees, J.a. “Migration and Optimal Income Taxes.” Journal of Public Economics, vol. 18, no. 3, Apr. 1982, pp. 319–341., doi:10.1016/0047-2727(82)90035-4.

“Neymar: Paris St-Germain Sign Barcelona Forward for World Record 222m Euros – BBC Sport.” BBC News, 3 Aug. 2017.

Palmitessa, Elio. “Managing Athletes Image Rights in Italy: Key Considerations for Structuring and Accounting under the New Tax Regime.” LawInSport, 28 Feb. 2019.

“Paris Saint-Germain Cleared of Breaking Uefa’s FFP Rules.” The Guardian, Reuters, 13 June 2018.

“PSG: Qatar Considering Pulling Funding from Ligue 1 Giants.” AS.com, 2 May 2019.

Sartori, Andrea. “From Madrid to Turin: Ronaldo Economics.” KPMG | Football Benchmark, 2018.

Shaw, Craig, and Zeynep Şentek. “Turkish Football Federation Admits Knowledge of €4 Million Payments with Unregistered Agents.” The Black Sea, European Investigative Collaborations, Dec. 2018.

Sunderland, Tom. “Cristiano Ronaldo Transfers to Juventus from Real Madrid for Reported £105M Fee.” Bleacher Report, 11 July 2018.

“Tax on Foreign Income.” GOV.UK, 8 Dec. 2014, www.gov.uk/tax-foreign-income/non-domiciled-residents.

“Taxes on Personal Income – Italy.” Tax Summaries on Individuals, PwC, 22 Jan. 2019.

“Financial Fair Play: All you need to know – UEFA.com.” UEFA.com, 30 June 2015.

“UEFA and FIFA Officials Accused of Being ‘Enablers’ of a Corrupt System | News | European Parliament.” UEFA and FIFA Officials Accused of Being “Enablers” of a Corrupt System | News | European Parliament, 26 Sept 2017.

Wise, Peter. “Jorge Mendes, Power Broker behind Football’s Elite.” Financial Times, 5 Sept. 2014.

“Wolves Boss Nuno Espirito Santo Brushes off Football Leaks Claims about Jorge Mendes Relationship.” Sky Sports, Sky Sports, 23 Nov. 2018.

“World Record Football Transfer Fees – BBC Sport.” BBC News, BBC, 2018.

Cases:

Robyn Rihanna Fenty and others v Arcadia Group Brands Ltd and another [2013] EWHC 2310

Sports Club plc v Inspector of Taxes [2000] STC (SCD) 443).

Union Royale Belge des Sociétés de Football Association ASBL v Jean-Marc Bosman (1995) C-415/93

Appendix A:

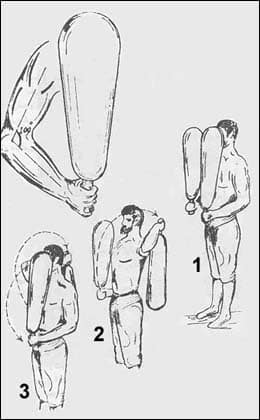

Tax Savings from an IRC (UK):

Scenario 1: No IRC – £5 million income from wages

£5,000,000 x (1-.45) = £2,750,000 net salary

Scenario 2: IRC – £4 million income from wages, £1 million licencing fee from IRC:

[£4,000,000 x (1-.45)] + [£1,000,000 x (1-.20)] = £3,000,000.

Scenario 2 (IRC) provides annual tax savings of £250,000.

Appendix B:

Tax Savings for Players from Agent Fee’s:

Assumptions – 10% agent fee + 21% VAT

Scenario 1: Fee’s Paid by Player

[£5,000,000 x (1-.45)] – [£500,000 agent fee] – [£500,000 x (0.21) VAT] = £2,145,000 net salary

Scenario 2: Fee’s Paid by Club

[£5,000,000 x (1-.45)] = £2,750,000 net salary

Scenario 2 costs the player £605,000 in net salary. Clubs can write off costs of agent fee’s as business expenses, but players cannot.